What is a Jumping Worm?

The term Jumping worm, refers to multiple species of Asian pheretimoid worm (Amynthas species) whose native range is in China, Japan and Korea. Jumping worms are a non-native and invasive type of earthworm. They are also known as ‘crazy worms’ or ‘snake worms’ for how quickly they can move and wiggle their bodies.

Jumping Worm

Jumping WormHow did they get here?

Earthworms were wiped out in North America after the last ice age. During early colonization, earthworms were brought over by European settlers for agriculture, garden and baiting use. Therefore, earthworms are non-native to Canada. While they have been around for a while, Jumping Worms are causing new concern for our natural environment because of how quickly they are taking over.

Why are Jumping Worms a problem?

Jumping worms are epi-endogeic, meaning they live primarily in organic matter in the top layer of soil. A healthy forest develops a layer of leaf litter called duff, that slowly decomposes over time and provides habitat and food for fungi, amphibians, birds, insects and native plants and trees.

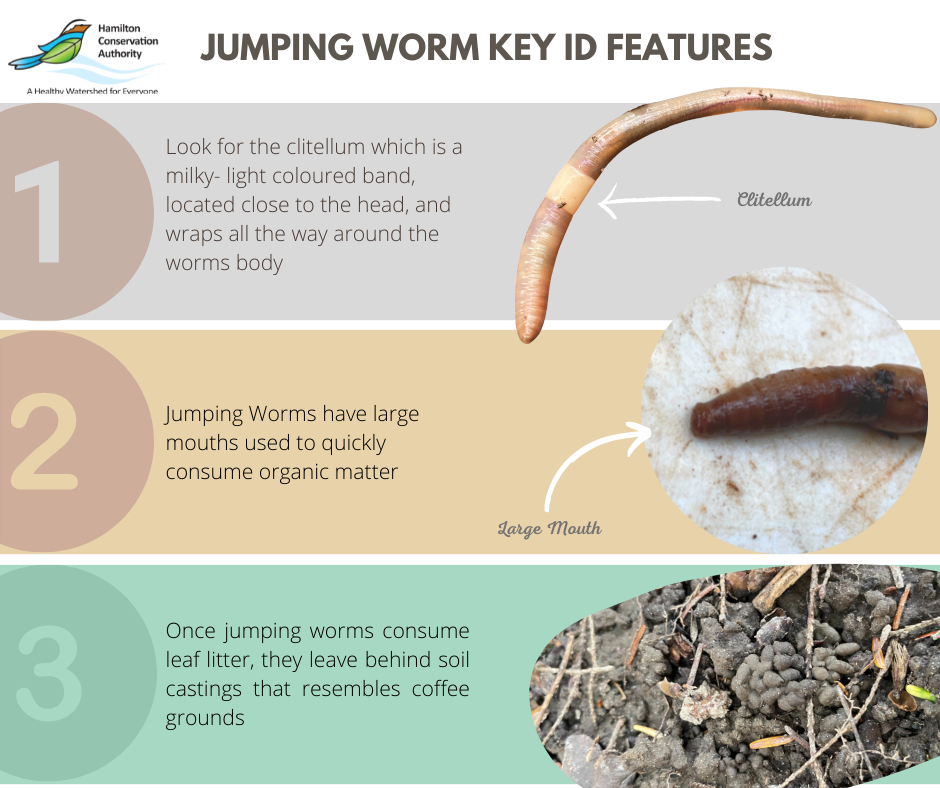

Jumping worms consume the duff, and are able to move and eat much more quickly than other worms. Eating the organic material removes the soils moisture and nutrients, and leaves behind loose, bare soil that is mostly castings (earthworm feces) resembling coarse coffee grounds. As a result, habitat and food are lost, and non-native plant species can quickly establish themselves. This prevents native trees from growing and leads to a loss of ecological integrity.

Jumping Worm Castings

Jumping Worm CastingsAren’t worms and castings good for the soil?

In gardens, earthworms are beneficial because they create compost with their castings, move nutrients into the soil and infiltrate water. In natural environments like forests however, earthworms are destructive, because they change the structure, chemistry and composition of soil. Jumping worm castings sit on the top layer of the soil, where plants cannot reach the nutrients. These changes make soil prone to erosion, negatively impacting the growth of native plants and trees, habitat and food for insects, fungi, birds and amphibians.

Lack of vegetation due to Jumping worms presence and their castings in the open areas.

Lack of vegetation due to Jumping worms presence and their castings in the open areas.Other Earthworm Species

- European Nightcrawler (Lumbricus terrestris) is a deep borrowing earthworm that creates vertical burrows, roughly 6-8 inches deep. These burrows create pore space, aeration and water infiltration. This earthworm pulls organic material from the surface, deep into the soil and makes nutrients available for plants. In the natural environment, the European Nightcrawler shares similar negative impacts as the jumping worm but at a slower pace. They are also commonly used as fishing bait.

- Red Wiggler (Eisenis fetida) is commonly used in gardens and for composting. They live and feed in the top layer of the soil and typically cannot survive cold winters.

How do they spread?

Jumping worms don’t need a mate to reproduce, therefore, one jumping worm can start a new population. They have a lifespan of one year, with adults maturing in June and producing egg cocoons from later summer into early fall. Adults dies in late fall and the cocoons survive over winter and hatch in spring.

Jumping worms cocoons are small, and spread very easily by sticking to shoes, garden equipment, and material such as mulch, top soil, pots, rootstocks and even mixed in with vermicompost worms or fishing bait.

How do I identify them? And what to do if I find them?

In June, mature Jumping worms are found within the leaf litter and are easy to identify by their distinct milky-white band called the clitellum that wraps fully around their body. The clitellum is the worms’ reproductive structure and is located close to the head.

Jumping worms are more active than other worms and will thrash or wiggle when disturbed to try and get away. As a defense mechanism they can even lose their tails. They also have a mouth larger than most earthworm species. Another key feature is bare soil with little to no vegetation growth – no other earthworm creates ground coffee-like casting.

How do I keep them out of my garden?

When purchasing new plants, carefully inspect the potting soil for any signs of jumping worms and their castings on the soil surface. When you are ready to plant, remove most of the soil from the roots and rinse the roots with water. Put the remaining soil into a garbage bin.

Ask your garden supplier where their source is coming from. Look for soil and mulch brands that are heat-treated. Jumping worms and their cocoons cannot survive temperatures above 40C for 3 days (Chang et. Al 2021).

- Never purchase Jumping worms for fishing bait or vermicomposting. Dispose of worms purchased for fishing bait in the trash and never release into them into the environment.

- Never dump garden waste or soil into natural areas.

- Never blow leaves into natural areas.

- Never move plants or soil to new places.

- Always stay on trails and clean your shoes after using trails.

- Keep pets on leash.

What to do if you have Jumping worms

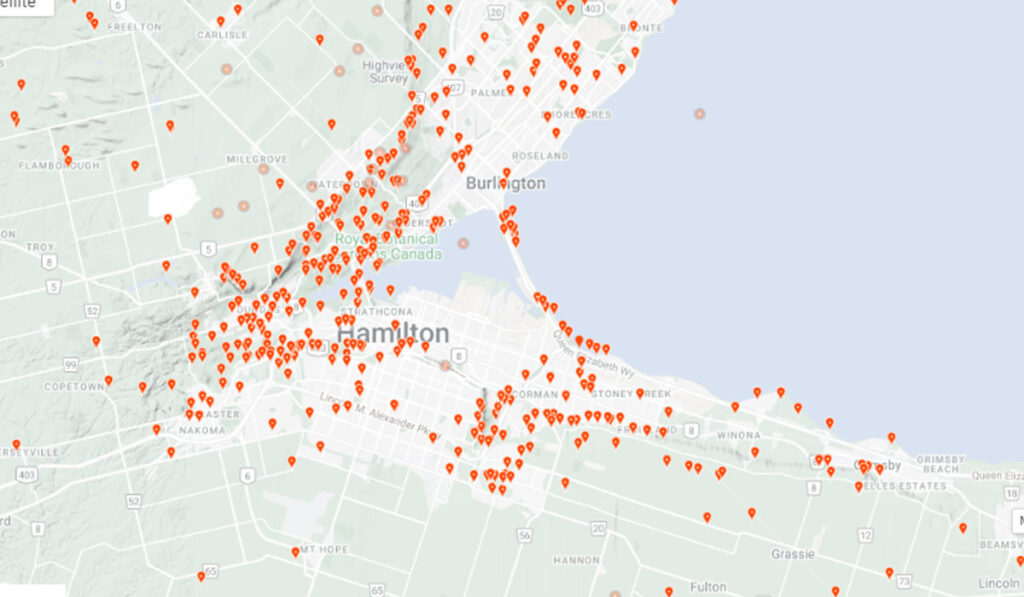

You can report jumping worms on iNaturalist, which helps scientists and professionals in the field keep track of local biodiversity. You can remove adults by euthanizing them in soapy water, vinegar, mustard powder or isopropyl alcohol, then dispose of into the garbage.

What to plant if you have Jumping worms

Some native plant species with deep-roots can do well in areas infested with jumping worms. Examples include Trout lily (Erthronium americanum), Jack in the Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), Blue Cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), and Christmas fern (Polystichum arcostichoides). Besides Blue Cohosh, these species are also deer resistant.

If you are looking to support or create a new garden, consider planting a prairie savanna garden that contains native grasses and wildflowers. Native grasses and wildflowers are deep-rooted and will do well in areas infested by jumping worms. You will also help support pollinators such as butterflies, bees and insects.

Resources and References

Worm Watch

Garden Resource: Joe Gardener

Jumping Worms in Ontario: Clean North

Invasive Species Centre

Ontario Invading Species Center

iNatuarlist

Chang, C. H., Bartz, M. L., Brown, G., Callaham, M. A., Cameron, E. K., Dávalos, A., … & Szlavecz, K. (2021). The second wave of earthworm invasions in North America: biology, environmental impacts, management and control of invasive jumping worms. Biological Invasions, 1-32.